|

|||||||||||||||

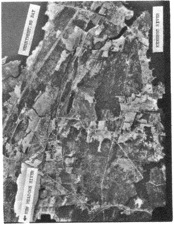

FROM The Best from American Canals - Number II, page 11* Written approximately 1980 By William E. Gerber "You who 'enjoy a strollin the country these crisp winter days can find no more interesting and enjoyable tramp than that along the old canal which was built over 100 years ago to connect the New Meadows and Kennebec Rivers” so wrote a reporter for the Bath Independent in 1911, almost seventy years ago. His words give evidence that a Iong-forgotten feature of the landscape north of Bath had survived in a quite recognizable form at least until then. The reporter had visited the canal a fewdays prior and had walked its ice from end to end. Tidal flow, unconstrained by causeways had kept this waterway open from the time of its construction; then about 120 years. In addition to describing the beauty of his own crisp winterstroll and recounting a little of the history, the reporter speculated about what an asset it would be to small boats if the canal could be reopened. Fate, aided by man, was not to be so constructive. In subsequent years, causeways were built across the Kennebec end of the canal to carry the North Bath and Lover's Retreat Roads. Likewise, a causeway was also built for the Bath-Brunswick Road. Together these structures choked off the flow that had for so long sustained the canal, leaving the adjacent waters to stagnate. Slowly the canal began to fill and disappear. Today, this waterway, once built by men of industry and vision, is little more than a wet scar on the earth. And Bath, which for more than 100 years became an island during each high tide, has once again become a peninsula. But not all traces of the canal are gone. Inspired by the reporter of long ago, this writer also made his pilgrimage to the old canaland walked its frozen waters. There was, of course, no way to confirm that it was once three or four feet deep and it certainly nolonger is. But in some places, the ice clearly exhibits the dimensions that history records; a width of 30 feet through much of its2 1/2 miles length, necking down to 20 feet at some points. Furthermore, Bath's peninsular status is still tenuous, at best. Theentire end to end joumey, except for perhaps half the length of a football field, can be made over the ice of the canal. Of course the walk is not so easy as it was 70 years ago. The northem section, between the North Bath and Lover's Retreat Roads, is stillkept open by the flow of Welch’s Creek (also known as Wittam's Creek). But from Lover's Retreat Road west and south to theheadwaters of the New Meadows River, the channel is thick with impeding scrub growth. Approaching the former crossing of theOld Brunswick Road, marsh grasses obscure most traces of the canal edges but south of this point, the route again becomesquite obvious. What are the origins of the canal? When was it built; by whom and for what purpose? It hasn't made the news in a long, long time;in fact, the Bath Independent's story of 1911 may have been the most recent significant news coverage. But a little diggingproduced the following: the first record of the canal concept is a petition to the General Court of the Commonwealth of Mas-sachusetts for permission to cut a canal from the head of the New Meadows River into Merrymeeting Bay. It was dated January1, 1786, and was signed by 98 citizens of Brunswick and Bath. (What a New Year's Party that must have been!). The purpose of the canal was to bring "Lumber and Masts directly into Casco Bay and to Falmouth without going to sea or running the hazard of going down that rapid torrent, the main Stream of the Kennebeck." The principle beneficiaries, of course, were to be the owners of the tidal mills along the New Meadows River. Timber local to the West Bath area was becoming scarce by this time and the canalwould give the mills access to logs which even then were being floated down the Androscoggin and Kennebec Rivers intoMerrymeetlng Bay. On this aerial photo, the route of the old canal, between the New Meadows and Kennebec Rivers, is clearly visible.

About four years later on March 5, 1790, the General Court passed an act authorizing the creation of a corporation to build the canal, listed the members of the corporation, and specified that no tolls would be required for public use. But on June 17th of thenext year , a second act was passed amending the list of corporate members and making provisions for the collection of tolls. It read in part: " A canal from the head of the New Meadows River to Merrymeeting Bay. .. the New Meadows Canal...that the saidcanal shall be kept open for the passing of boats, rafts and other water crafts, and for all persons who may wish to pass ortransact business therein, they paying the following toll; ...every boat...of one ton, the sum of nine pence, and in the sameproportion for vessels or boats of greater or less burthen not exceeding six shillings for any such vessel or boat. For every thousand feet of boards in rafts four pence half penny; and in the same proportion for all other kinds of lumber.” On March 22nd, 1793, the court passed an act recognizing that the canal had been opened "… from the New Meadows River tothe waters of the river Kennebec, a little below Merrymeeting Bay, at a place called Welch’s Creek, it having been found impracticable to open a canal directly to the Bay aforesaid, by reason of rocks and other obstructions." This act also empowered the proprietors to keep the canal open and to enjoy all rights and privileges. Based upon this act, it appears that the canal wasprobably completed the preceding year: i.e., in 1792.

One John Peterson, must have been the driving force behind the canal or perhaps became its principle user He built a damacross the upper cove, apparently in the vicinity of the present Maine Central Railroad Bridge, and established a grist mill at the eastern end and saw mills at the western end. Eventually the New Meadows Canal became unofficially known as the PetersonCanal, and a road on the west side still bears his name. The records don't tell us much about how the canal was operated. Among a number of people interviewed around the turn of the century, several insisted that the canal had never been completed and no logs had ever been transported through it. Otherscould recall their parents talking about going down to the locks but no conclusive evidence of locks or tidal gates has ever been found. It is not clear that anyone has ever seriously looked for them. There is a remnant of some kind of stone and mortarstructure in the canal, near the north end but it is clearly not a lock and probably not a tide gate. One man, however, rememberedhis father telling how hard he had worked as a boy poling logs up through the canal, His father was born in 1795 and if he workedon the canal when he was only 10 years old, then the canal operated for at least 12 or 13 years. Of the various accounts, this oneseems reasonably plausible. It is further substantiated by at least one other statement that under favorable conditions, two raftsof logs placed end to end, each raft composed of six large logs laid side by side, each log not less than 60 feet long, were easilyfloated through the canal. Nevertheless, all evidence suggests that the canal was less than a resounding success. One problem concerned the difference in the times of high tide at each end of the canal. Typically, the canal could be used for only about three hours of each tide cycle. Other limiting factors seem to have been the insufficient depth to which the builders blasted through the ledge at the summit and the apparent lack of any flow control such as might be afforded by locks or tide gates. Whatever problems the canal may have had, the concept of a waterway between the two rivers was a good one and would be quite useful today if it were reestablished. (The author, William E. Gerber, resides at 16 Princess Ave., Chelmsford, Mass. 01863)

|

Watercolors by

Sarah Stapler

Sarah Stapler

Last

Updated:

Visitors:

TWICE-A-DAY ISLAND

TWICE-A-DAY ISLAND